The first time that I heard about MIT was in class six.

Around that time, the word 'hack' had only one definition: it was the verb that some kids would employ to describe what they were doing to the computers in our computer lab, when they attacked its keyboards vigourously. The word 'hacker' evoked, in common imagination, visuals of a nefarious, yet somehow benign, teenager who could break into any device that contained a circuit. 'Hacking', then, was not what little kids who were interested in technology wanted to do. It was definitely not what the studious sorts wanted to do.

I was a studious child, and most of the new friends I made in class six, on entering 'senior school', were of a similar sort. In a conversation with one of these new friends, I was asked if I planned to prepare to enter an IIT. The response has escaped from memory, but what remains is the answer I got from my friend, upon turning the question around. It was in equal parts surprising and illuminating.

"No, I will go to MIT. Massachusetts."

I had difficulty pronouncing it then; I am compelled to admit that I have difficulty pronouncing it now.

Seven years later, the friend went on to duly join an IIT. I made two attempts to, but could not. Life then seemed as if it had deviated from ideal trajectory; I continued to mope until I realised, after multiple months, that life has no measurable trajectory. To be in a state of contentment, while simultaneously trying to measure "progress" in life seems as impossible as the measurement proven to be impossible, decades ago, by Werner Heisenberg. Physics was imploring me to move on, and, in the middle of the first semester in college, the changed definition of 'hack' came to my rescue.

The connotations of the commission of cyber crime were now replaced by the American college custom – popularised by multiple sequences in The Social Network – of spending unbroken long hours of writing code to build something. These informal sessions driven purely by interest soon turned into formal, performative and competitive coding events, one hosted by each college. They would involve 24, or in some cases, 36 hours of continuous programming in teams, at the end of which, a panel of judges would declare the winner.

It is a social convention to name any event involving the performance of an activity for an unnaturally long duration after the first and most famous one of this sort: a marathon. Despite having recently been completed in under two hours, the burden attached to the word is such that all unreasonably lengthy human endeavours will forever be equated to marathons.The events, thus, became popular as 'hackathons.'

In October 2016 – the middle of the first semester in college – I made the first of another set of two attempts. These were directed towards getting into MIT; specifically and far less ambitiously as the preceding statement may sound, they were directed towards getting accepted to attend HackMIT. I did not make it, so I tried my hand at a lesser hackathon. MHacks is the University of Michigan's hackathon; I applied as part of a team with some of my friends from school, each of which was now a student at an American University. We ended up getting selected; I ended up, with some support from my own college, travelling to Detroit as perhaps the only international-student attendee of that hackathon. However, we did not win anything significant.

Close to two months ago, the same team decided to make a second attempt at getting accepted to attend HackMIT.

MIT is located in a city known as Cambridge, separated from Boston by the Charles River. Inside Cambridge, it coexists with Harvard University, creating a university city without, perhaps, an equal. A parent, though, exists across the Atlantic: Cambridgeshire — more popularly just Cambridge — in England is what inspired the naming of this city, since the university there inspired the creation of Harvard almost four centuries ago.

On receiving confirmation that we had made it, a trip to Cambridge became imminent. Since I would be travelling from India, like all good Indian tourists, I decided to add a few days of doing nothing much to the end of my two-day itinerary. Truly great friendship, it seems to me, is the comfort of being able to not do too much in each other's presence. To not feel the imagined burden of having to do anything: even silence is acceptable, familiar and enjoyable. A few days without a specific agenda seemed, thus, a pleasant and perfectly acceptable proposition to all.

If the origins of this friendship are to be analysed, the foundations would emerge in football.

We were all fans of the sport; consequently, we all became teenagers interested in the 'FIFA' series of video games. An obsession with watching the attractive European football abundantly available on television and playing the hyper-realistic games on computers and consoles is what, I imagine, helped a large number of teenagers make friends at the time. In our case, football continues to pepper conversation, as I suspect it always will.

A footballing analogy came to mind when we considered our chances at the competition: This was HackMIT - surely the congregation of the greatest and the most skilled teams in America – and probably the world – at one place.We felt we were faced with Pep Guardiola's Barcelona from the late 2000s – the greatest football team in the world, some say, of all time. Thus, we decided to emulate Jose Mourinho's Inter Milan.

It is widely believed that when Inter Milan, managed by Jose Mourinho, won the greatest football club competition in Europe in 2010, they far outdid themselves. This was due to a militaristic approach employed by them throughout the competition: they went in against difficult opponents with a clear strategy; they stuck to it throughout ninety minutes, and they ground out results. In one word, they were pragmatic.

The FIFA series of games has had another significant influence on the lives of multiple children: they are now adults whose tastes in music have been disproportionately influenced by the playlists' curated for that game. Multiple hundreds of hours on repeat - whilst playing the game – have meant that those songs, and those bands, have created a lasting sense of familiarity that is unshakeable. For me, one specific artist has stood out: Two Door Cinema Club. I was introduced to them by the game in 2010, and remain a dedicated fan, still.

A fantastic coincidence saw the band being scheduled to play in Boston on one of the additional days I had placed in the itinerary. At the expense of sounding clichéd, attending that concert has become the first instance of the crossing out of a bucket list item. I did not have too long a list at all; I definitely had no expectations of any of those events ever truly coming to pass. Thus, the completely mundane visit of a band to a city, to me, was a miracle.

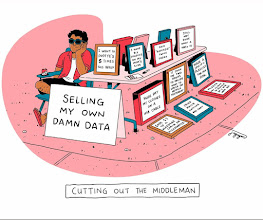

Another miracle had preceded this one entirely. In emulating Inter's pragmatism, we decided to target one specific prize out of the 15 or so available to win. All our efforts were directed towards becoming the best 'hack' that was centred around the blockchain, whilst providing a solution to urban problems. We came up with 'Argonaut': a data exchange platform to ethically sell personal data in exchange for cryptocurrency. This webcomic I saw a few days later perfectly, and a bit humorously, encapsulates the idea. The miracle was that we ended up winning.

The remnant of my days in Cambridge became a window into what life would be like as a student there. Ambulating through the city, which doubles as the Harvard campus, it became clear that if there is a field of study in the world, there is a center at Harvard University dedicated to studying it. The 17th century buildings exist in perfect symmetry with gleaming modern additions; the greatest facilities in the world that are completely accessible to students and even guests: a sense of trust in the public at large that is altogether absent in my lived experience. A Steinway & Sons piano was allowed to be sampled at the Center for Music; a daunting 'Smith Center' allowed a visitor like me space to sit and work in peace, as if I belonged. To top it all, I even managed to attend a class on Indian history, taught by former Member of Parliament, Sugata Bose.

To summarise the experience of life in Cambridge, I can only say that it is so perfect that signs of imperfection soon became pleasing. Despite having been to other, more developed parts of the world before, I had never before felt that I had somehow found the ideal. Perhaps the way the community in Cambridge is centred around knowledge – and the pursuit of all forms of it – hit a personal chord. On my last day there, I heard a bus let out a large horn; I even counted one instance of a car encroaching onto the pedestrians' crossing. Without romanticising it, I only wish to say that the imperfection felt familiar. It was a hint of reality in a world that felt a bit unreal.

I was told that people join Harvard and MIT as students and then spend lifetimes there: going on to earn higher degrees and eventually earning their livelihood teaching. A few days there made the popularity of this path very apparent: given a choice, I imagine it would be very, very difficult to leave.

Thankfully then, I had no choice.