Cities are like people. In “meeting” either, first impressions are crucial. One false move — one bad experience — may cause a relationship drastically different from what it may have been.

It all depends, therefore, on the introduction.

The spectacular cities of the world have mastered the art of the perfect introduction. The entry — regardless of mode — is always stunning: The trains, seemingly from the future, arrive, perfectly on-time, to stations: structures which are the embodiment of a spectacular past. The airports are massive; amazing simply through sheer scale. The roads are a flawless grey, inscribed with symmetric symbols and signage; the buildings that rise up from the sides, resplendent and imposing, drive home the first impression that everything is perfect; everything just works.

It is carefully engineered, the perfect introduction. The end-product of bold vision; crafted through meticulous design.

Delhi, however, makes it abundantly clear on entry — regardless, again, of mode — that there will be no perfect introduction. Everything, and indeed anything, goes, here, and it is up to you to get used to this idea.

The trains from the past arrive — never on-time — to stations: exhibits of a colonial past and the poverty it has left behind. The airport — a spectacular one, no less — is an attempt to nudge the city into mending its ways: rolling out the red carpet in a city which has welcomed visitors for years with sewers and hills of garbage. A noble attempt; the hill, however, was always going to outlive the carpet.

Things are different today. The first sign is an on-time arrival of the Kalka Shatabdi to New Delhi; a first in my two years of being a regular patron. Next in the rapidly unraveling series of unlikely events is a newly installed false ceiling on Platform #1 : the ultimate proclamation of prosperity in aspirational India.

It is due to this signalling that I decide to experiment. The traditional exit — one involving dodging swarms of autowallahs on the filthy streets of Paharganj — is given a miss, in favour of acting on a hunch.

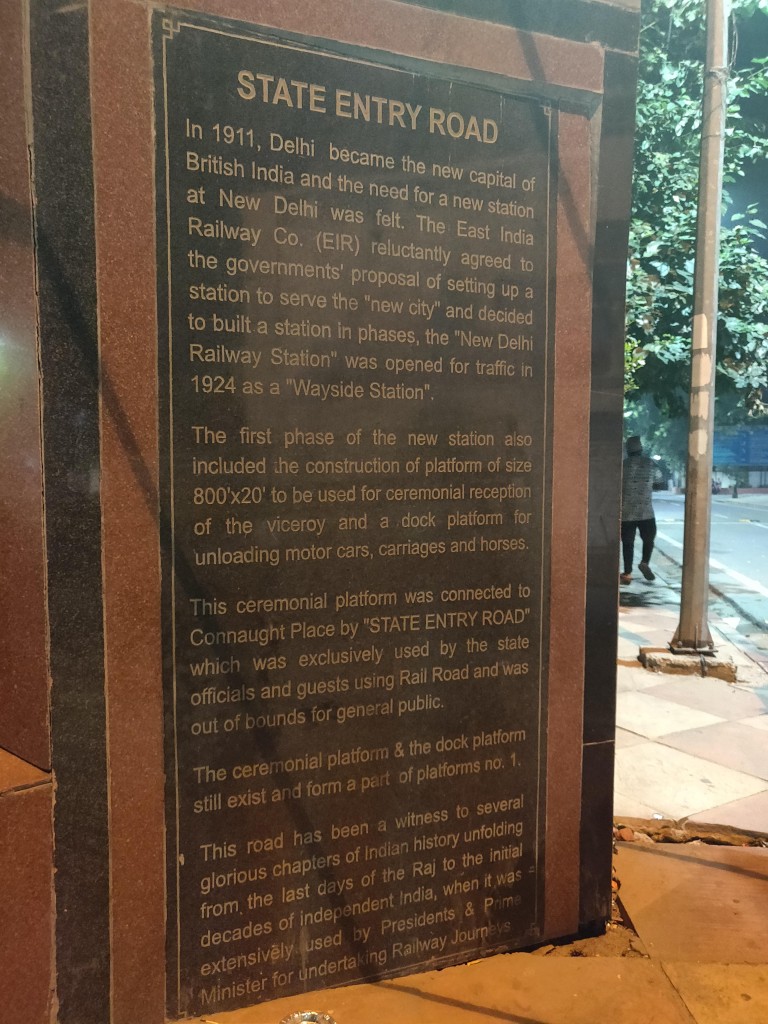

It pays off. At the other extreme on Platform #1 — a five-minute straight walk down from where I deboard — are located the iron gates of the State Entry road. As an intimidating notice hung to the gates declares, they are usually “closed due to security reasons”. Today, they are flung open. Hanging to one side is the steel frame carrying the notice – barely noticeable.

The tree-lined avenue — State Entry Road — I find myself on is typical of the more important parts of this city: It is spotless, well-lit and feels welcoming for a pedestrian like me. It is elite enough to inspire safety and anxiety simultaneously: the only other people on the broad footpath are the late-night elderly walkers; residents of the railway flats. Railway policemen make infrequent appearances on this ten-minute stretch. They are bunched together outside the Delhi Divisional Rail Manager’s office that also finds refuge on this road: What if they tell me I can’t be here?

No such untoward hostility greets me. The familiar traffic of the Connaught Circus appears in the distance; the pole of the Central Park flag stands in the centre of the visual.

A five-minute walk, straight ahead, leads us underground, through Gate #2 of Rajiv Chowk Metro station, to the warm embrace of the Delhi Metro. Getting home is a breeze.

The ease of it all is jarring.

What results is the confirmation of a long-held belief about cities. We may think we know them, but we never really know them. There is always room to continue probing. In that, to my mind, cities are like people.

To the benevolent authority which decided to let subjects exit through the State Entry, I remain extremely grateful. This mode of rendezvous with the city will go on to replace all others.

It is, after all, a perfect introduction. Far from accurate, but perfect.