It is an interesting sociological experiment to watch the same film in two different cities.

During the first viewing, 'Yesterday' drew large, hearty laughs from the audience in Vasant Kunj, Delhi. Understandably so: it is a comedy centred around a fictional world where only one man remembers 'The Beatles' and their songs.

In Mumbai though, a much-larger, packed hall remained largely silent throughout the couple of hours that the film went on for. This made for an initial impression of the city as filled with people who don't laugh a lot. Perhaps their minds were elsewhere: consumed by clients, sales and deals; or perhaps they were generally on edge, considering that the city was on an 'orange alert', and it continued to pour outside.

Perhaps they were just very polite.

Laughing out loud in a theatre is, after all, an impolite act: it will obstruct, albeit for a few seconds, the viewing experience of those around. The bar of acceptability – how many dialogues are okay to miss? – is variable across places: in Mumbai, perhaps, that bar is set at absolute zero.

Is 48 hours sufficient to justify conclusions about a city and its society? Probably not, but in that sense, is 48 years sufficient? We are all fooled by randomness, and thus, a short time duration allows for fewer coin-toss events to occur and skew one's impressions. An example: the choice of window to look out through – left or right? – will often dictate one's experience aboard a long-distance train journey, taking it from vastly uneventful to thoroughly insightful.

The 16 hours I spent aboard August Kranti Rajdhani making my way to Mumbai Central oscillated between serenity and anxiety at regular intervals: pristine views of the monsoon over western and central India, the calming sound of the gently rocking carriage speeding along, and the nerve-wracking visuals attached to #MumbaiRains: a confused sensory offering to the mind, which could only draw the conclusion that I was, very peacefully, making my way to imminent danger.

I drew comfort from how remarkably at ease most of the others in the coach were; halfway through the night, however, this observation explained itself in a distressing manner: they were all on their way towards a far lesser adventure than visiting Mumbai during peak rainfall - a visit to Ranthambore National Park, for which they got off at Sawai Madhopur Junction.

The train suddenly felt empty: I had no neighbours for what remained of the 16 hours, and I had to rely on the train, the views and Monisha Rajesh's 'Around India in 80 trains' for composure. A section of her book talked about touching down for the first time at the platform in Mumbai and instantly realising that this was multiple cities rolled into one; another one described her experience taking a local train during rush hour, when the train experiences what is known as 'super dense crush load.' As the rain steadily grew in intensity, soon – having crossed rivers and creeks – I too found myself touching down at Andheri and boarding a local train to Bandra. Despite being in Mumbai for the first time, these names seemed very familiar.

Another pleasant surprise presented itself as I looked at the Google Maps summary of my little commute: for the first time in all my years of using Google Maps, I had found that the public transport alternative threw up a shorter time of arrival than driving. In Delhi, the decision of using public transport always has to be driven by a rejection of practical interest. An extra 20 or so minutes has to be allowed for, purely to be able to practise living – in a city with poorly developed public transport infrastructure – with the hope that one day it will improve.

The only little hiccup arrived when I had to deboard at Bandra: the passengers ahead of me expertly got off before the train had halted; calls from behind ordered me to do the same. I decided that if I was not to be a bottleneck, I had no other alternative, and jumped.

The only preparation I had for this stunt was getting off Delhi Transport Corporation buses, where the driver never really stops the bus: you are expected to be able to jump and run your momentum off on the road. This past experience proved largely sufficient, although I did not expect to be lambasted by other passengers for not following proper protocol in the way I jumped. I told them I had spent under an hour in Mumbai, and that I came from Delhi where you had to wait for train doors to open. They understood, but quipped back saying that in the time the metro doors open, Mumbai folk make it to work. A searing indictment of my superiority, which would, over the remainder of the two days, be repeatedly pummelled by the city, albeit very politely.

Traffic discipline, well-paved footpaths, mild-mannered people mostly minding their business and yet helpful if required; a tone of idyllic restraint in conversation even when the pace of the city around is relentless. My experience of such a paradox is limited to the island that is Lutyens' Delhi: I was told that, in Mumbai too, I must not use my experience of the more southern and central parts of the city as a true picture of the nature of the entirety. That, I will accept, is true; however, my limited travel through Mumbai has left me with an oddly unfamiliar sense of being surrounded by polite society.

Of the multiple possible explanations that arose in the film theatre, thus, it is the last one that now seems the most correct.

The film ends with a statement that is, of course, perfectly relevant in its context, but which seemed stunningly appropriate for my own visit too. Thus, the line has remained stuck in my mind ever since I saw the film again.

You can't sing songs about places you've never been to.

For more than six years, I have been brandishing a particular piece of Mumbai history as my favourite quiz question; one I use most often in conversations about quizzing. The renaming of the Victoria Terminus to Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus by a Railway Ministry with Suresh Kalmadi at the helm in 1996, and it being described as the "biggest sex-change operation in Indian history" by a contemporary edition of the Outlook Magazine. Standing beside the building, I could only think of this, and all the other quiz questions I've made about places I've never been to – and how, despite a great love for heritage, architecture and trains, being at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (a Maharaj has been added only recently) was especially significant because of the imaginary ties to it I felt I had.

Cinema also tells us that helping a friend move into a new apartment in a new city is an especially significant moment in life. In this case, however, the setting up of the room and the tour around the locality having been completed, the farewell was farely limited. The usual clapping of hands, along with the implicit promise of staying intermittently in touch, and seeing each other again whenever we would be in the hometown at the same time. This reduction in stature of that moment is perhaps the greatest testimony to how affordable internet and affordable flights have curiously combined to eliminate the tyranny of distance from our lives. There are rarely any more true sunsets.

There are no true sunsets in Mumbai as well: at 11:30 PM, the city remained as at work as it would be twelve hours prior; perhaps even more. This was one observation I was expecting to make based on everything one hears about the city, and it was the one that felt the most stark. It was so astonishing because of the low base standard I had for comparison: the capital city of India turns off much earlier, and roaming around at night is far from being as pleasant. A cup of chai could be had from a Chaayos outlet located right on the street, and a stroll along the sea could be had even at midnight: a kind of experience altogether absent from my vocabulary, built out of living in Delhi for most of my life.

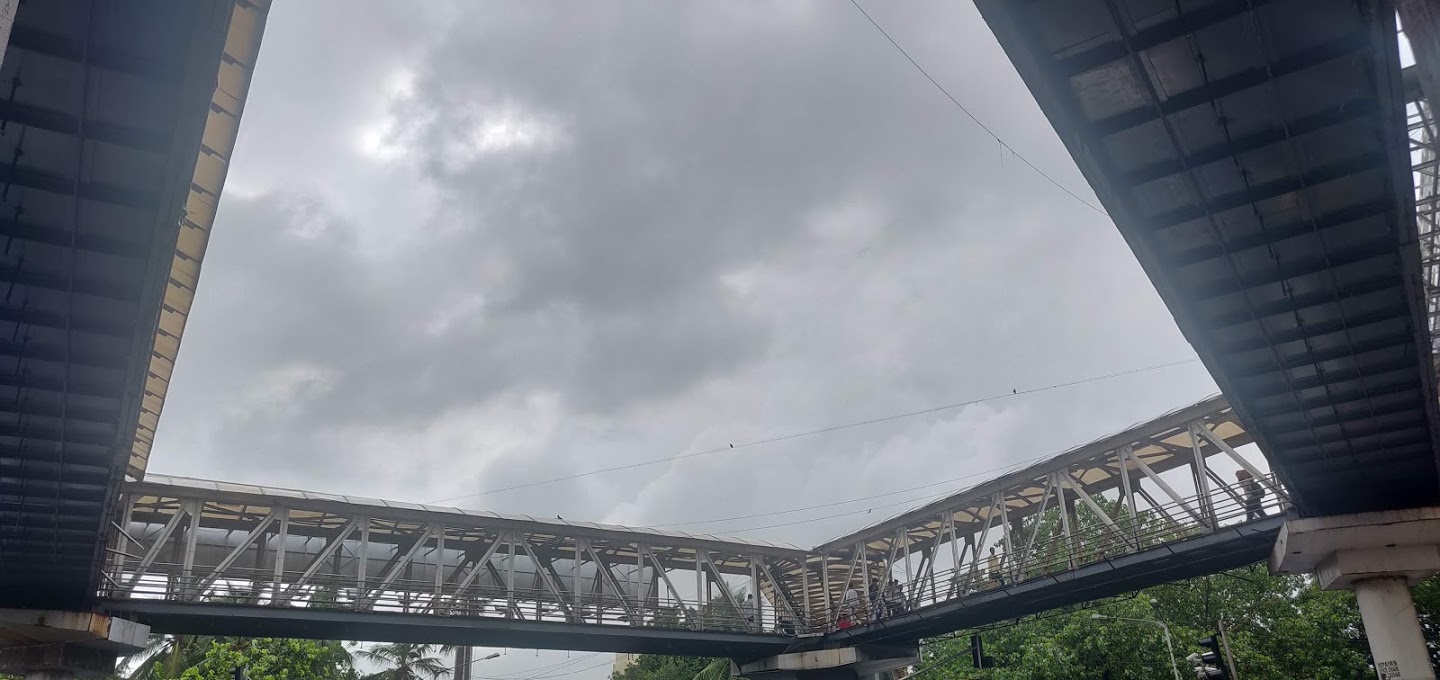

The ending of both the film and the trip left me with a bolstered belief in the prospect of improvement. Mumbai, it seemed, has invested in all the right things: a giant clean up operation going on round the clock, as evidenced by trucks, big and small, with a "Clean Up!" plastered on their sides in English and Marathi; well-maintained sidewalks in most parts, and overhead pedestrian infrastructure in parts where sidewalks were absent. It was distressing and joyful at the same time, because it meant that if Delhi is a sad song, we can make it better.