In May, I spent a week in Leh. More than anything else, I remember it as being a string of embarassing revelations.

The first occurred before the trip began: turns out that flights to Leh from Delhi are far shorter, cheaper and more frequent than I expected.

When the plane descends through pristine peaks onto the Leh airstrip – just an hour after taking off through Delhi’s haze – you look outside with disbelief. It shouldn’t have been this easy to get to a place this spectacular.

The Indian Army greets passengers on landing in to the Kushok Bukola Rinpoche military airfield. This might soon change, with a modern civilian airport next to it under construction. This is clearly necessary: the current building is far from sufficient to handle the influx. With an Indian Passport though, you are able to skip at least the “foreigners’ registration” line. A rare feeling of privilege as an Indian in airports.

The Border Roads Organisation’s roads await outside. On childhood family trips, I would dread hours of driving on mountainous roads and wish that we could somehow get there, without having to suffer through getting there. The BRO is famous for its signboards that bear witty messages all along their roads. One of them says, “Difficult journeys lead to beautiful destinations.”

The flight to Leh, in that context, feels almost like cheating.

Given these unfair means, all those who travel via air must spend at least one day doing nothing much except acclimatising to the altitude. For us, this meant socialising with the staff and guests at the hotel, and attempting to photograph the spectacular Leh Palace and its surrounding structures. One of these was a hilltop monastery with a trail of steps leading to it, which was a 15 minute jog away according to Rigzin, the caretaker.

“It might take you 45 minutes, though.” He is the kind of person who is constantly grinning, so it is impossible to be offended by anything he says.

He was far from wrong, though. On day one, even the simple flight of steps to our room was a challenge for the lungs. The monastery - within reach only through a camera. A stroke of luck then, that I had decided to bring along a decent one, and not just wing it with my smartphone.

Days before going, a sudden inspiration to not carry my smartphone along had struck. Monk mode, as they say. I had tried to do something similar before a visit to Meghalaya more than a year ago. My family disagreed on both occasions, so both attempts remained unsuccessful.

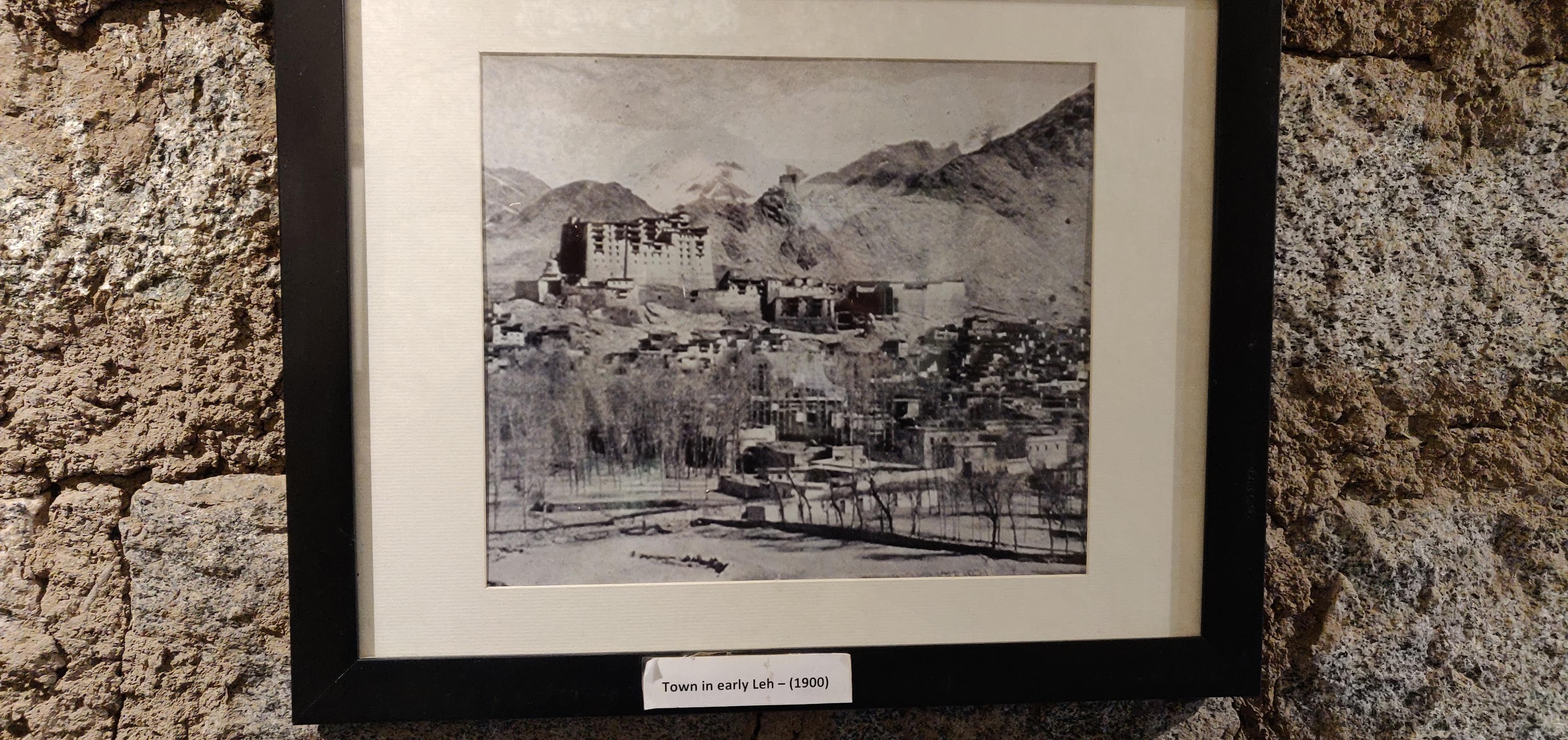

The Ladakh landscape is a far cry from those Meghalayan forests, though: barren, talismanic mountains rise up beside you, coexisting seamlessly with civilisation. Nothing represents this relationship better than the three hundred year old rock castle which towers over the city, built on the side of a mountain in mud-brick and wood.

Soon enough, a second embarrassing revelation. It became clear to me that the smartphone I was forced to carry along is nothing better than a brick for the next week anyway. Prepaid SIM cards don’t work here due to Ladakh’s former association with the troubled state of Jammu & Kashmir. What good is a smartphone without coverage? The Meghalaya dream has come to pass.

Every previous mention of Leh to me was as a pitstop in adventurers’ chronicles, on their way to more heady destinations. Therefore, expectations from the city were few. I was suspicious about it even resembling a city, and the agenda of the week was intentionally minimal: get work done.

This remains the most embarrassing revelation from that week: Leh is a city all right, and a spectacularly liveable one at that. My days there added up to a resounding defiance of any and all of my expectations.

Every morning, we would take a wonderful walk down to the central market: a large, pedestrian only square with shops new and old; cafes and restaurants, a refurbished large mosque and along with it, an entry to the old city. Every evening, the walk back up meant asking for a lift, which a kind stranger would invariably give. Unimaginable in the city I’m from.

Surprises abound here. One morning, it is in the form of a hidden history museum – perhaps the most exceptionally designed one I’ve ever been to. One evening, it is to find a chapter of Alliançe Francaise hidden deep in the lanes of the old city. Another evening, it is to see architectural conservation efforts of the highest quality, quietly underway. On my final morning, it is to find the impossibly far hilltop monastery within physical reach.

Does this extraordinary city cultivate this extraordinary society, or is it the other way around?

Tourists make an undeniable contribution too: when it gets too cold in Leh, and there are no tourists, there is no economy. The chef at the cafe I frequented in my week told me that he moves to Goa to work in a café there through the winter.

“The birds, the fish, the mammals: they all migrate. Except us. Why should we not?”

This past year of being geographically untethered has presented me with no answers to his question. I hope to be able to continue looking.